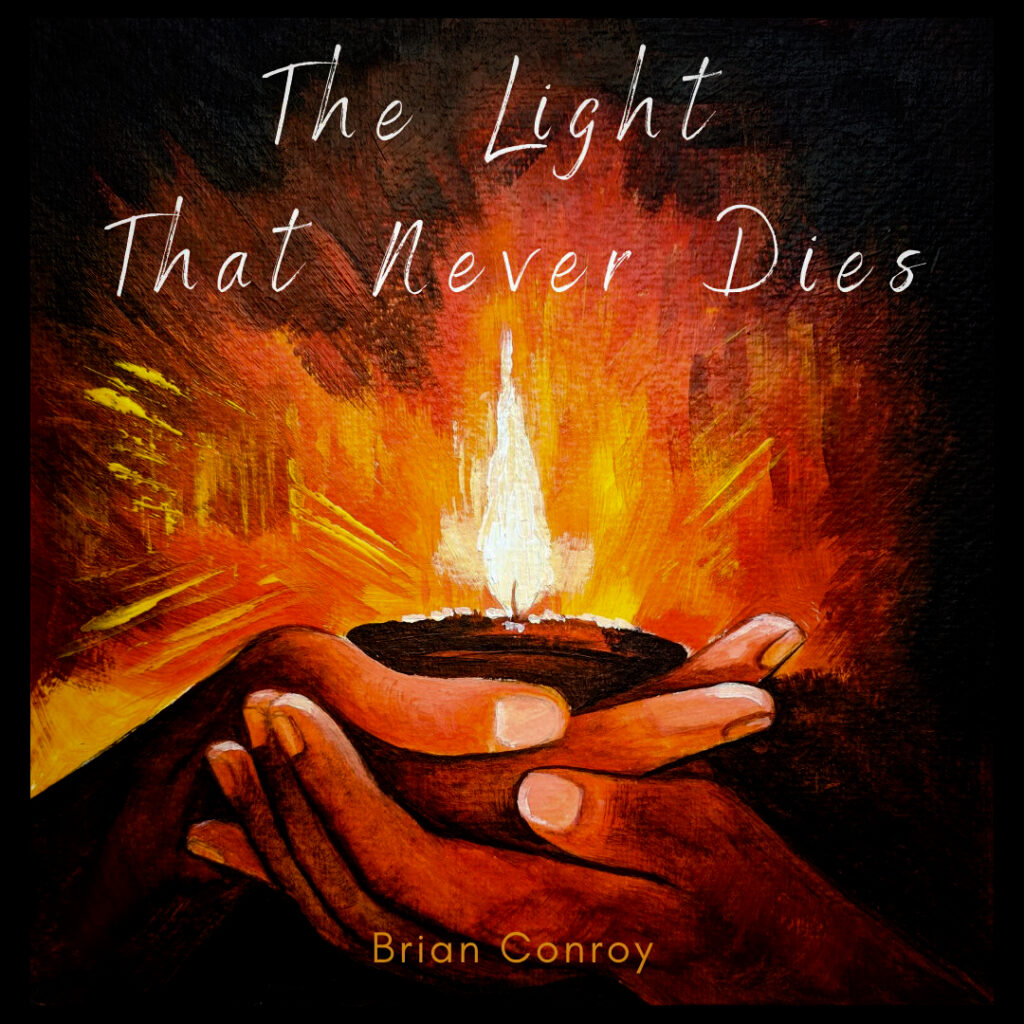

The Light That Never Dies

The Light That Never Dies

Buddhist stories told by Brian Conroy

Introduction

The Light That Never Dies is a collection of twenty-six Buddhist tales told by storyteller Brian Conroy. Blending humor and wisdom, these concise parables illustrate principles such as patience, compassion, giving, empathetic joy, Right Action and Right Understanding. Holy fools and wise sages show the pitfalls of greed, anger and delusion, the implications of cause and effect, and the benefits of holding the Five Precepts. Many of the legendary figures of Buddhism are represented in these tales, including Shakyamuni Buddha; Putai, the “Laughing Buddha”; Layman Pang and his daughter Lingzhao; Devadatta; Angulimala; as well as compassionate nuns, heroic deer, and diligent hummingbirds and quail. The Light That Never Dies is delightful celebration of Buddhist folklore.

Download music

Spirit in the Cave of the Heart music album is available for free through Good Karma Music by sharing a story of your act of kindness.

30 seconds demo clips

Notes and lyrics of the songs

In the summer of 2021, I served as a mentor for Service Space’s summer internship program. I was matched up with fourteen-year-old Alakh Kapadia. In his application for the internship, Alakh stated that he had been inspired by reading my book, Stepping Stones. For his main internship project, he proposed recording a CD of my stories. Over two sessions, working in Alakh’s home recording studio, we recorded the stories, which were engineered and edited by Alakh. The Light That Never Dies is the result of Alakh’s vision come to fruition.

This Indian parable is a reminder that each person bears responsibility for making the world a better place, every single day. Not only do the people living in the small village of this story understand this, they practice it, every single day.

A mind overflowing with discriminating thoughts is the greatest obstacle to spiritual practice. This well-known Zen parable is part of the Buddhist oral tradition. I first encountered it in Zen Flesh, Zen Bones by Paul Reps.

In this Chinese folktale, there’s a stark contrast between heaven and hell: In hell we serve ourselves; in heaven we serve others.

There are several variations on this tale in world folklore. In each, selfless deeds get rewarded, and deeds performed with selfish intent reap unintended consequences. This tale comes from China.

Another Chinese folktale, this story illustrates how our flaws reveal our uniqueness, and our beauty emerges from our broken parts. As Leonard Cohen sang, “There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.”

An original story based on biographical details of the life of 9th century Chinese sage, Putai. Through his lifelong practice of empathetic joy, Putai discovered that the more he gave, the more he had to give.

Adapted from a tale in Zen Wisdom Stories by Koh Kok Kiang. A kind-hearted nun offers everything she owns to a thief in order to rob him of his desire to steal.

This story comes from The Jataka tales, a collection of stories dating back to 300-400 B.C. detailing the Buddha’s previous incarnations. Each Jataka teaches a principle or virtue. In this story, the Buddha is reborn as a compassionate deer whose example teaches a prince to respect and protect all living things—the foundation of Buddhist teachings.

As the Dharma Master of this tale shows by his actions, a wise person knows when to follow the path of least resistance. The original source of this story is unknown.

Each of us possesses a lantern to light our path. Making sure that the candle within the lantern shines brightly requires persistence and mindfulness. Original source unknown.

King Bimbisara was a protector and benefactor of the Buddha who lived during the 5th century B.C. This story is one of many anecdotes ascribed to the Buddha’s teaching. The poor woman’s offering is present in multiple versions of the tale. The slightly altered ending was inspired by Eknath Easwaran’s version, retold in his translation of The Dhammapada

This Korean folktale shows how the power of compassion can transform living beings.

This delightful little anecdote comes from The Sayings of Layman Pang. Layman Pang lived during the 8th century and was the first person to use the phrase “chop wood, carry water.” I have reworded Lingzhao’s final phrase to make the ending more accessible.

The majority of Jataka Tales feature animal characters. In each tale, the Buddha—referred to as the Bodhisattva—is identified at the end as one of the main characters. In this Jataka, featuring only human characters, the Bodhisattva is reborn as a student whose moral grounding prevents him from breaking the precept against stealing.

A hermit urges two children to act responsibly. Will they do the right thing? The answer is in their hands. Original source unknown.

This story comes from The Panchatantra, a collection of Indian fables dating from 200-300 B.C. The fable makes the distinction between the wisdom of common sense and the limitations—and potential danger—of the intellect alone.

This allegory explains why we shout when we are angry. Sometimes attributed to Indian mystic, Meher Baba, there is no evidence he actually told the story. The confusion likely derives from Meher Baba’s 44-year vow of silence and his lectures cautioning against harsh speech.

Angulimala is one of the great villains of Buddhist literature. His story can be found in Indian, Chinese and Tibetan sources. This version is adapted from the Angulimala Sutta, a section of the Majjhima Nikaya.

This Taoist tale of a man blinded to everything but his greed comes from the Liezi, a 5th century B.C. text, authored by Lie Yukou.

Another anecdote from the vast body of stories of the Buddha’s teaching.

Recently, Kenyan storyteller Wakanyi Hoffman and I discovered that we both tell a very similar variant of this tale. Wakanyi’s version originates in Africa; mine comes from China. One school of folklore theory maintains that similar stories from varied cultures emerged more or less concurrently without being passed from one culture to the next. Since we all share the same collective unconscious, similar archetypes and themes appear throughout international folklore. This story’s image of a tiny living creature working diligently, utilizing her small potential to solve a seemingly insurmountable problem, is a metaphor for the path of cultivation.

In the same way that a mantra is recited to develop mindfulness, the protagonist of this story cultivates patience by drawing with his brush the character of patience one hundred times. Adapted from a Chinese folktale.

Paradise is where you find it. You may already live there! Adapted from a story written by my friend, storyteller and author, Steve Sanfield.

A well-known Buddhist anecdote from the 13th century text, The Collection of Sand and Pebbles by Shasekishu. Eighth century Chan Master Taolin, was known as the “Bird Nest Monk.” His teaching is easy to comprehend, but far harder to put into practice.

About the artist Brian Conroy

Brian Conroy is the founder of the Buddhist Storytelling Circle, a group of storytellers from the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery who perform at interfaith and Buddhist gatherings. For thirty-five years Brian taught theater and public speaking in the public schools in San Jose. He received his M.A. in Folklore from San Jose State University, where he taught storytelling for ten years. As a storyteller Brian has performed at festivals and conferences including the National Storytelling Festival, The Parliament for the World’s Religions, and The Buddhist Storytelling Festival. Brian first encountered Venerable Master Hsuan Hua in 1976 and took refuge with the Master in 1994. He is the author of Stepping Stones, a collection of Buddhist parables, and Prince Dighavu an adaptation of a traditional wisdom tale.

Production

Recording Engineer/Project Manager: Alakh Kapadia

Cover Artwork and Design: Rupali Bhuva

Special Thanks To: Nipun Mehta, Audrey Lin, Yogen and Bhumika Kapadia